150 Years of Germany — How the Empire Shaped the Modern Nation State

As executive director of GAHF, I am often asked to provide an overview of Germany’s history. This is an understandable question considering that some 50 million Americans today claim German descent.

However, it’s not an easy task, as Germany’s history is complex, and often begins with the question of how one defines the nation. The boundaries of the present-day Federal Republic do not include many historically German regions, and the majority of German-speaking immigrants arrived well before its founding. But how far back should we go?

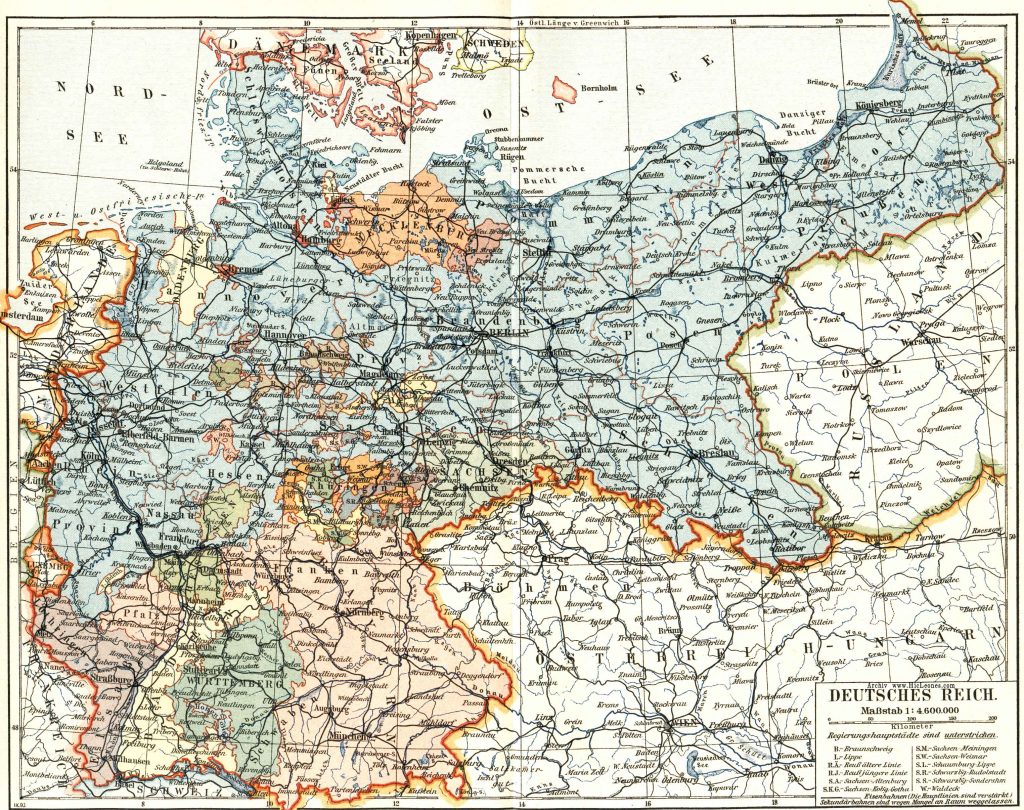

As an avid history lover, I have often resorted to the year 1871. On Jan. 18, 1871 William I, King of Prussia, accepted to be proclaimed Emperor of Germany in the Palace of Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors, once the residence of the French kings. The Franco-Prussian War was still being fought, and Paris was besieged by German troops. The proclamation was a display of pomp and circumstance worthy of the historic occasion, but it was also designed as a deliberate snub of the French enemy, still the most powerful military force on the continent, but now defeated by a German alliance. Thus began the German Empire, which unified 26 German states, including four kingdoms, six grand duchies, five duchies, seven principalities, three free Hanseatic cities, and one imperial territory, and which lasted until the end of World War I when the monarchy became a republic.

Ironically, the artist Anton von Werner, who memorialized the proclamation of Imperial Germany with his famous painting featuring William I in an elevated position and Prince Otto von Bismarck, the master strategist and longest-serving chancellor, almost in the center, along with countless sovereigns, aristocrats, and high-ranking military officers in their colorful uniforms, sympathized with more liberal ideas. He smuggled a message into his painting: In the foreground, wearing a white uniform, is a simple guardsman, Louis Stellmacher, representing the people who were subjects of this empire, and yet had no voice in its creation.

The idea of German unification was not new—it had been around for decades—and a predecessor, the German Confederation, which included Austria, had been created by an act of the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The rivalry between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire led to a number of problems, and eventually the dissolution of the Confederation and the exclusion of Austria in 1866. Bismarck had always envisioned the Prussian Royal House of Hohenzollern as the leader of the German states and King William I as primus inter pares, or first among equals. In 1867, he founded the North German Federation that comprised the 22 states north of the Main River. A skillful negotiator, a master of Realpolitik, but also a clever manipulator, Bismarck not only fought three deliberate wars (the Second Schleswig War in 1864, the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which established Prussian hegemony, and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71) to forcefully pave the way for German unification, he eventually managed to convince the four southern Germany states to join the Federation by taking advantage of the patriotic fervour created by the Franco-Prussian War.

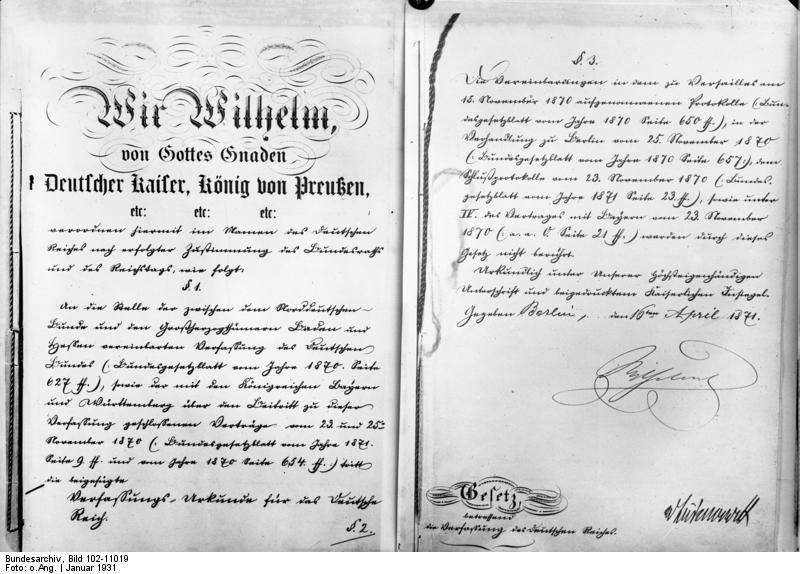

While the top-down implementation of this first German nation state was probably not the desired path for many educated nationalists and progressive forces who had participated in the 1848 Revolution, it was nonetheless a milestone, and 1871 brought Germany not one, but two constitutions: The Constitution of the German Confederation on Jan. 1, followed by the German Constitution, which was adopted by the parliament, or Reichstag, on April 14 and went into effect on May 4, 1871.

The Constitution, with the Emperor at the top, was inspired by the Frankfurt Assembly of 1848, and gave a measure of representation and rights to the people. Apart from granting national citizenship to all residents of the Empire, it established civil procedures and rights, and gave men over the age of 25 the right to vote in national elections. Women were still excluded from political participation, although the constitution did not explicitly state this, but women’s rights made some strides when women not only gained access to higher secondary education and universities, but also campaigned for lower prices for consumer goods and social improvements. Speaking of social reforms, it was once again Chancellor Bismarck who, showing his pragmatic side, on June 15, 1883, implemented mandatory health insurance for industrial workers, added accident insurance in 1884, and eventually government pension funds. His motivation was to keep the working population appeased, but his willingness to compromise and adopt the policies of the social democrats created a stronger, better, and more democratic society.

The birth of a nation is quite often not a peaceful process, the United States itself was born out of an act of rebellion followed by a war of independence, and the same is true for other countries. Germany’s great European neighbors, France and the United Kingdom, had completed the process of national unification a century or two earlier, but while they flourished the fallout and trauma from the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) did not just hold Germany back, it actually caused a regression. While Germans benefited culturally and politically from Enlightenment and Rationalism, it was delayed, and thus Germans were unable to develop a strong liberal tradition like their English counterparts.

The German Empire was a product of its time, marked by authoritarianism, imperialism and militarism, but it also inspired great progress and held the roots of democracy, the Weimar Republic, and the modern Federal Republic of Germany. History and its lessons should never be forgotten, because to do so often leads to repeating mistakes of the past.

-Katja Sipple-