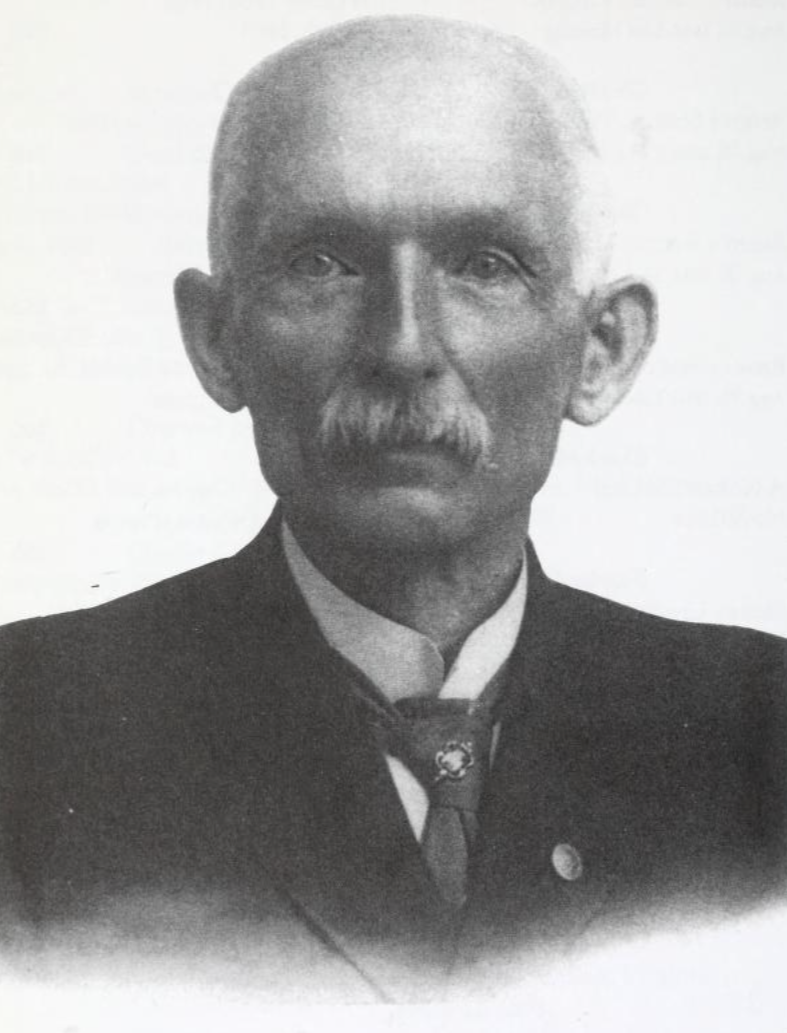

Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben was born to a military family in Magdeburg, Prussia, on September 17th, 1730. His father was Wilhelm Augustin von Steuben, a Royal Prussian Engineer Captain who served in both the Russo-Turkish War of 1735-1739 and the War of Austrian Succession. Due to his father’s military prominence, Steuben regularly observed his father’s military campaigns and was exposed to the military and the art of warfare from a very early age.

At 17, von Steuben enlisted in the Prussian army and would go on to serve in the Seven Years’ War. At the outbreak of the war in 1756, Steuben served as a second lieutenant within the Prussian army and battled at both the Siege of Prague (1757) and the Battle of Kunersdorf (1759). Throughout the war, Steuben would quickly rise in rank, eventually reaching the rank of captain in the Prussian army. As a captain, Steuben served on the general staff of Frederick the Great, advising the King of Prussia at both the Third Siege of Kolberg (1761) and the Siege of Schweidnitz (1762) towards the end of the Seven Years’ War.

With the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben retired from the army when the Prussian military reduced its size at the war’s end. Steuben would remain unemployed until 1764, when he became a Hofmarschall, or court marshall, for Prince Josef Friedrich Wilhelm of Hohenzollern-Hechingen. During this period in Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Steuben received the Cross of the Order of Fidelity and was honored with the title of baron. Despite working in the court of the principality, Steuben still desired to serve in the military. It is unknown whether he voluntarily retired from his post at the prince’s court or was obliged to leave due to rumors alleging he was homosexual. Still, after his leave, he began to search for employment in European armies.

In 1777, an acquaintance of Steuben’s, Claude Louis, Comte de Saint-Germain, introduced the retired Prussian captain to Benjamin Franklin. During their meeting, Franklin informed Steuben of the Continental Army’s need for military professionals; however, Franklin was not authorized to grant rank within the Continental Army and could only suggest that Steuben travel to America for employment within the army on his own. Out of desperation, Steuben accepted the offer, and in turn, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to Congress and General George Washington introducing them to Steuben. However, in Franklin’s letter, Franklin falsely stated that Steuben achieved the rank of lieutenant general during his time in the Prussian army. Whether this error was due to mistranslation or an attempt to make Steuben a stronger candidate for the Continental Army is unknown.

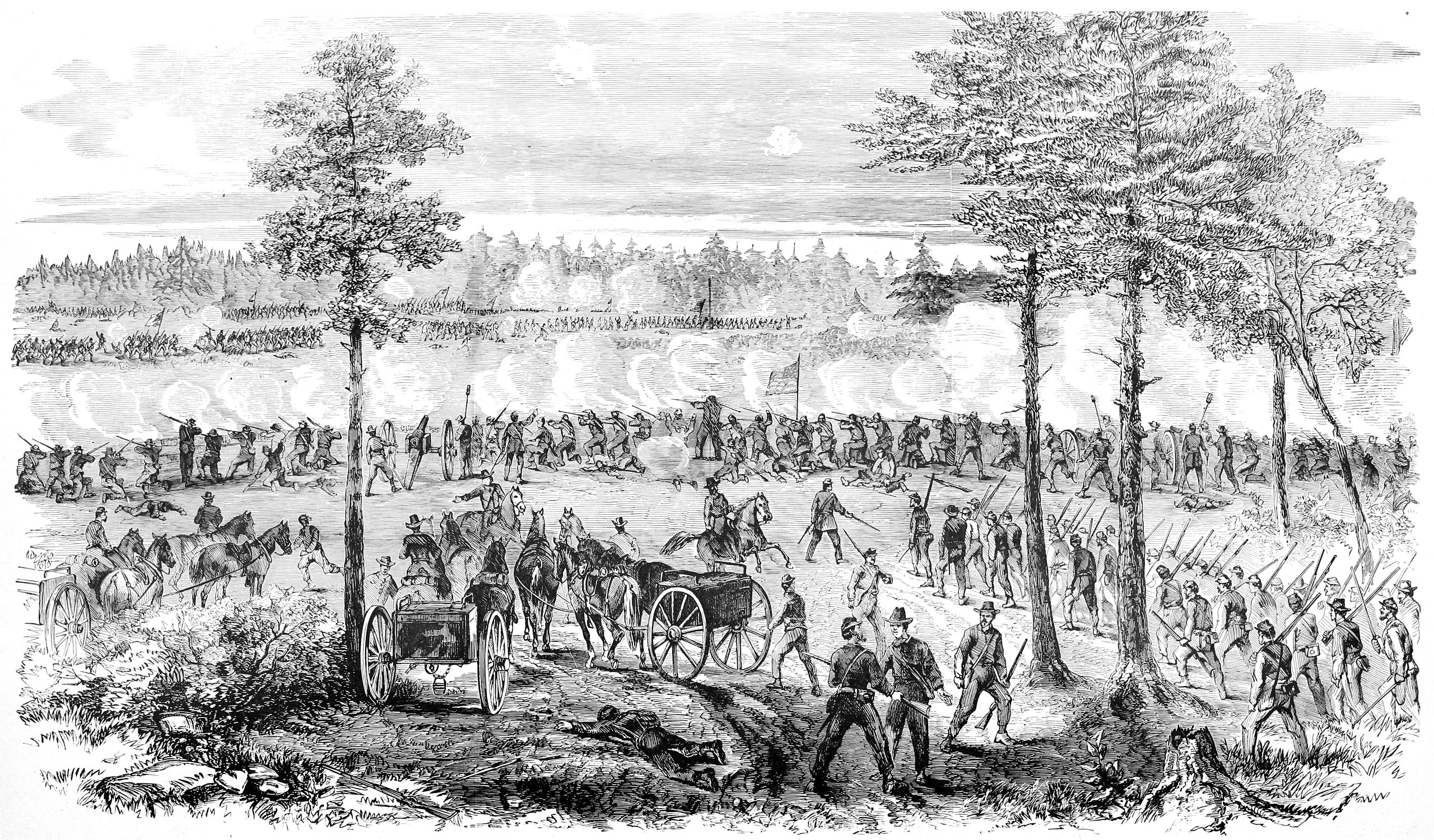

Nonetheless, impressed with his credentials, Steuben was inducted into the Continental Army in late 1777. In February 1778, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben arrived at Valley Forge and reported for duty. At Valley Forge, Steuben was appointed as an inspector general of the Valley Forge encampment. With this role, Steuben set new standards for the organization and training of the Continental Army. Before Steuben’s arrival to the Continental Army, each colony utilized different drills and maneuvers for their armed forces. Seeing this practice, Steuben created a standard method that would allow for the entirety of the army to be more coordinated. Steuben used the commander-in-chief’s honor guard to teach this standardized method, which consisted of soldiers from various regiments from each colony. Steuben utilized the honor guard as a model company to demonstrate each new drill. In turn, honor guard members would train other regiments, thus setting a standard for drills across the whole army. In addition to standardizing methods throughout the Continental Army, Steuben instructed the men on proper sanitation and weaponry usage, transforming the Continental Army into a legitimate fighting force.

Impressed with Steuben’s accomplishments, General George Washington appointed Steuben as inspector general of the army with the rank of major general in May 1778. In the summer of 1778, Steuben’s methods and training showcased their immense value in the Battles of Stony Point, Barren Hill, and Monmouth, which resulted in victories and minimized casualties for the Continental Army.

In the winter of 1778, Steuben left the army and resided in Philadelphia to write his book, Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, a manuscript on the training methods he had implemented at Valley Forge. The book became standard in the US military and was utilized in the army until 1814.

In April 1779, Steuben rejoined the Continental Army and their southern campaign and served as an instructor and supply officer for the South Continental Army. At the final campaign in Yorktown, Steuben commanded one of the three divisions of the Continental Army, which fought in key battles that led the British to surrender. Steuben aided the army’s demobilization at the end of the American Revolutionary War and established a defense plan for the newly created United States.

In March 1784, von Steuben resigned from the military and became a citizen of the United States. He settled in New York on land granted to him for military service. This piece of land later became the town of Steuben, New York, which was named in honor of his contributions to the nation. In his estate, Steuben resided with his two aide-de-camps, William North and Benjamin Walker, both of whom he met while serving at Valley Forge. Historians suspect that Steuben, North, and Walker may have been in a homosexual relationship together. However, there is no confirmation. For the remainder of his life, he served as president of the German Society of the City of New York, which aided German immigrants in the United States. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben died on November 28th, 1794 at his estate. He was laid to rest in a grove marked by a monument that can be visited today.