Auto Draft

Ferdinand F. Rohm

Civil War

Biography

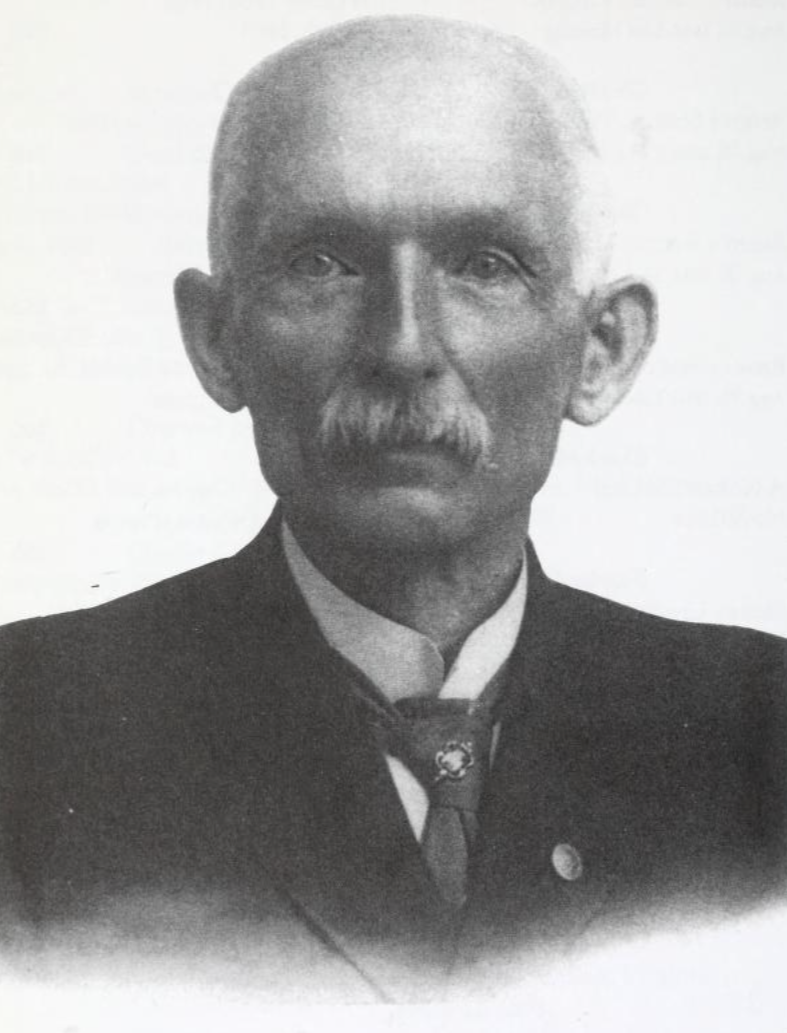

Ferdinand Frederick Rohm was a native German who served as a soldier for the Union Army during the American Civil War. Rohm served as the chief bugler for the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment from September 1862 to June 1865 and was present for multiple campaigns and thirty-eight battles and military operations during the course of the war. For his heroism at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station, Rohm was awarded the Medal of Honor; the highest military decoration in the United States Armed Forces.

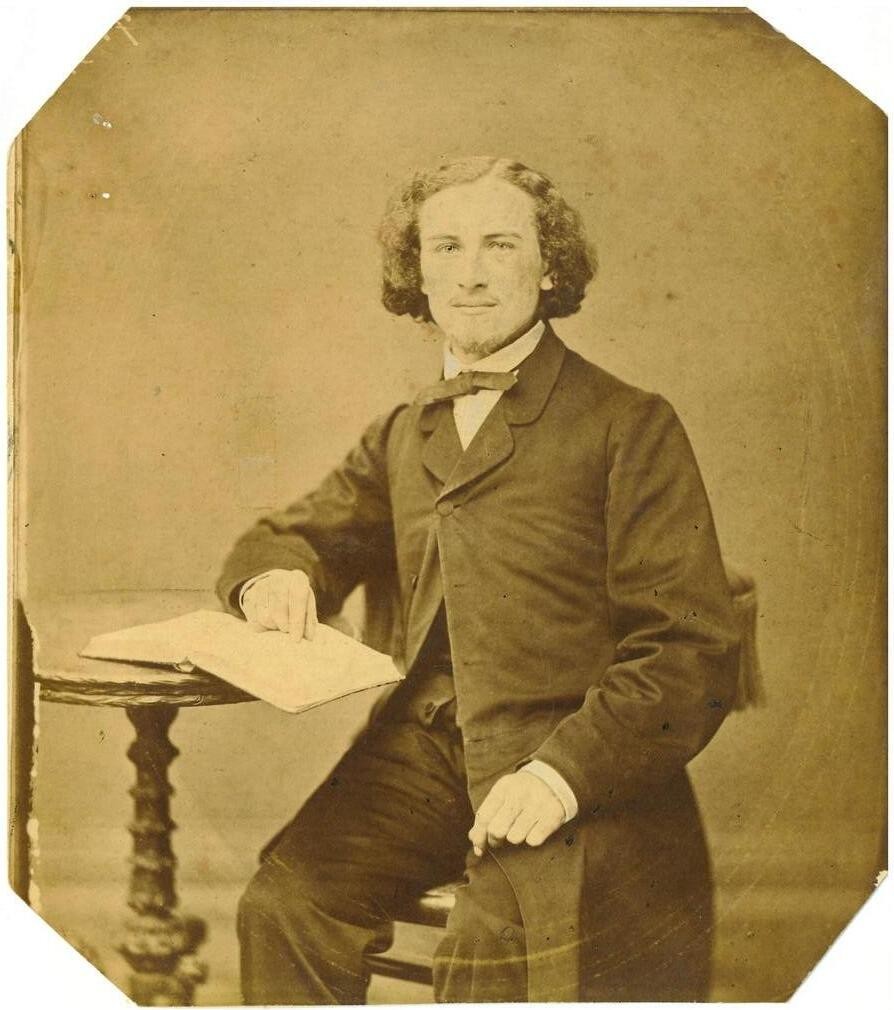

Ferdinand Rohm was born in Esslingen in the Kingdom of Württemberg on Aug. 30th, 1843. It is unknown when exactly Rohm immigrated to the United States, however, he was one of the many German immigrants that left the disunited German states who would go on to serve the Union Army during the American Civil War.

In September of 1862, Rohm enlisted in service of the Union Army in Juniata County, Pennsylvania; where he was assigned to the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. After a year of enlistment, Rohm was transferred from F Company to the central command as chief bugler for the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry regiment in 1863.

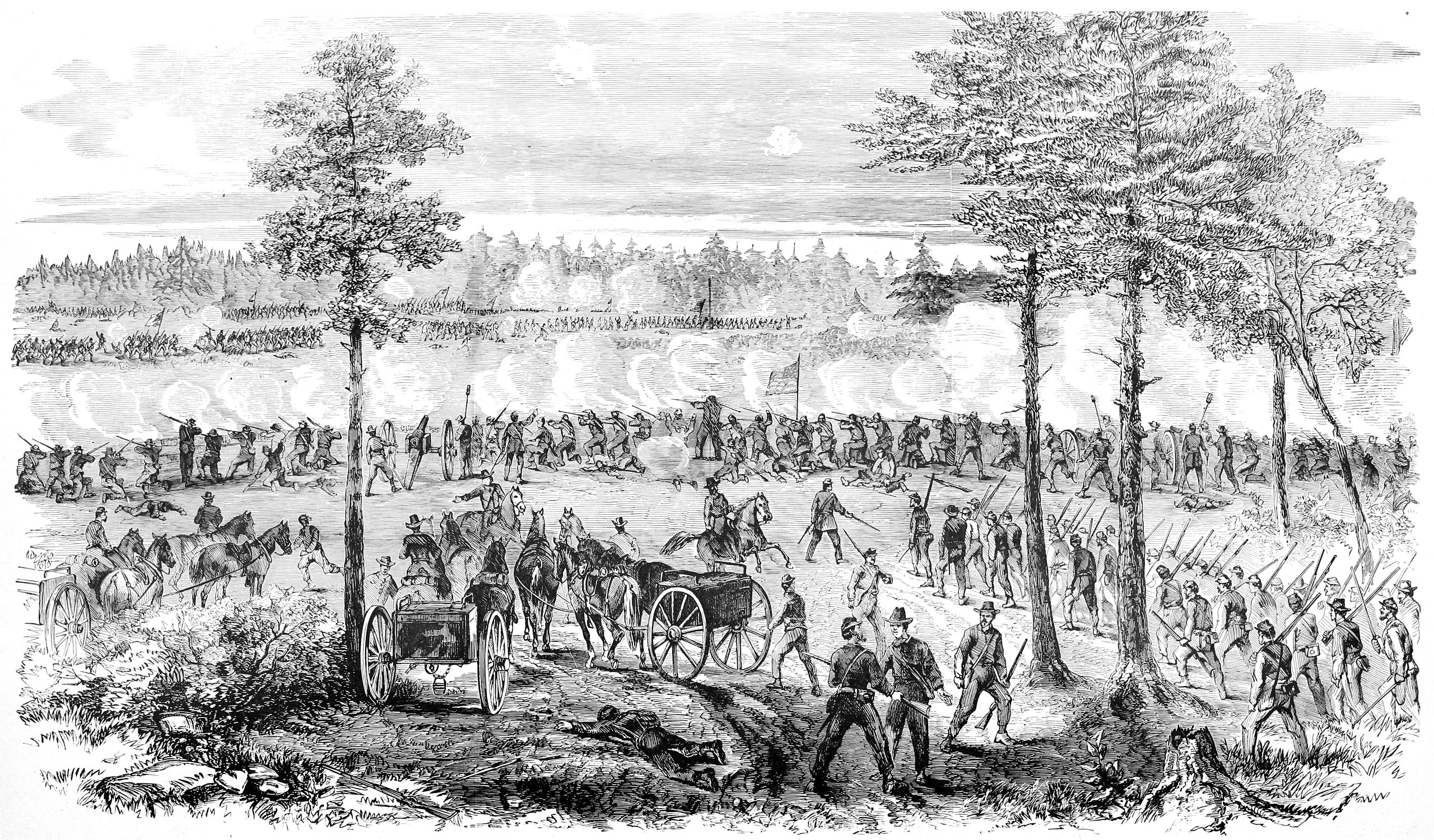

Prior to the Civil War, armed forces used drums and fifes to communicate messages across the battlefield and organize troop movements. However, due to many of the battles of the Civil War being staged in the hills and forests of the United States rather than open fields, it was difficult for soldiers to interpret the messages over consistent artillery, musket fire, and close quarters combat. The introduction of the bugle allowed for messages to travel greater distances across the battlefield and became indispensable to maneuver skirmishers during combat.

The chief bugler was the bugler at the regimental level, responsible for instructing, training, and drilling the buglers attached to the companies of the regiment. Instructions and calls from the commanding officers were broadcasted with the chief bugler and further echoed by the buglers in their respective companies.

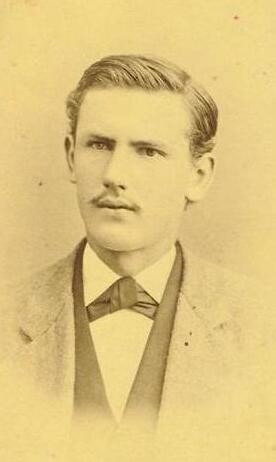

As chief bugler, Ferdinand Rohm played an instrumental role on the battlefield in facilitating the orders from the commanding officers to the companies of the regiment. For the remaining two years of war, Rohm served as the chief bugler of 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry and directed the regiment in combat for thirty-eight operations and battles throughout seven different military campaigns. Rohm was present for many prominent battles during the Civil War including as the Battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863, the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864, and the Battle of Cold Harbor in late May of 1864. However, despite being present for these prominent battles, Rohm is most known for his actions at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station in Virginia of August 1864.

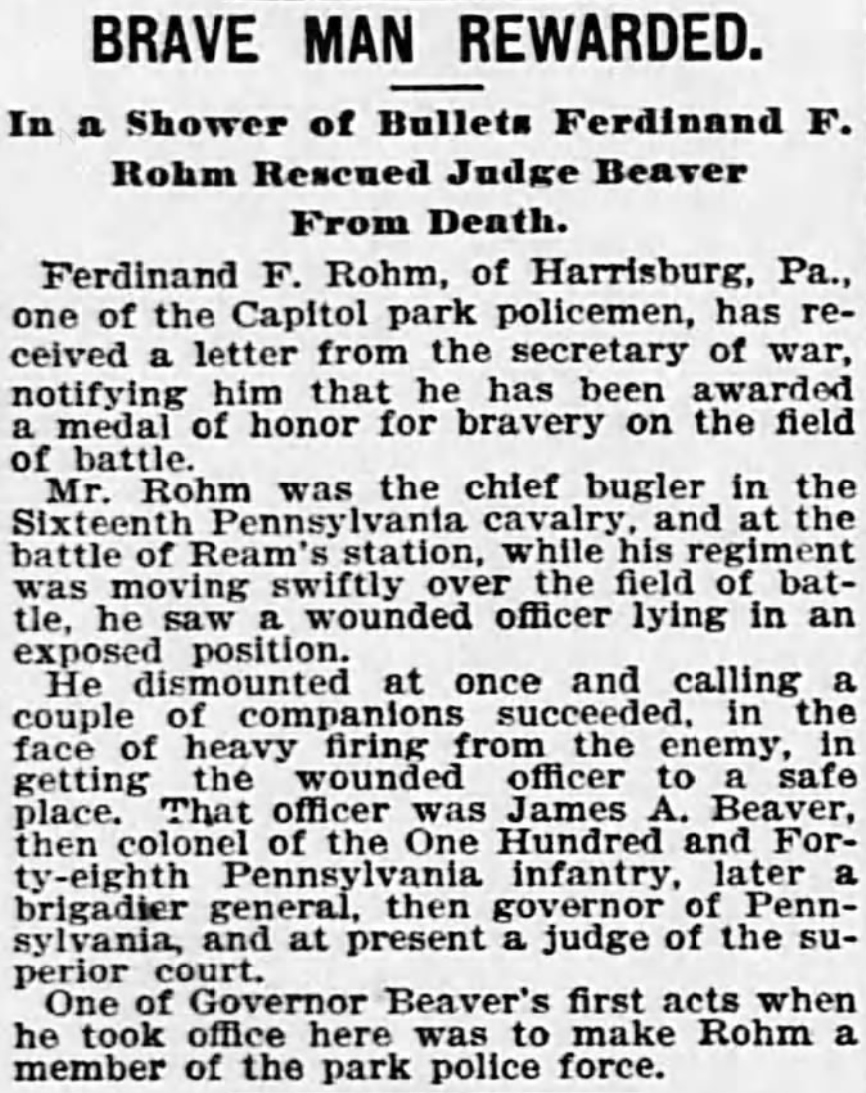

During the Second Battle of Ream’s Station, Chief Bugler Rohm performed an act of bravery and valor in which during an attack from Confederate forces, Rohm, rather than seeking immediate cover from enemy fire, remained on the battlefield to assist an officer, Colonel James A. Beaver, who in 1887 would become the 20th governor of Pennsylvania. In 1894, Rohm reflected on his service and heroic act in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette:

“Directly after [the rebels’] retreat a heavy skirmish line of the rebels appeared. It was followed by a line of battle which opened fire on us. We suffered considerably from their fire and fell back toward our infantry. Just after we had passed a small piece of woods about ten yards from our line of entrenchments I noticed a field officer lying on his back in the dust in the middle of the road, waving his hand toward us. My attention was particularly attracted to him by the fine, new dress uniform and the shoulder straps of a colonel which he wore. As I drew nearer I saw he was wounded. I knew if we did not take him along he would be captured by the enemy or killed. I jumped on my horse and upon examination saw he was shot through the thigh. I had three of our pioneers dismount and assist.”

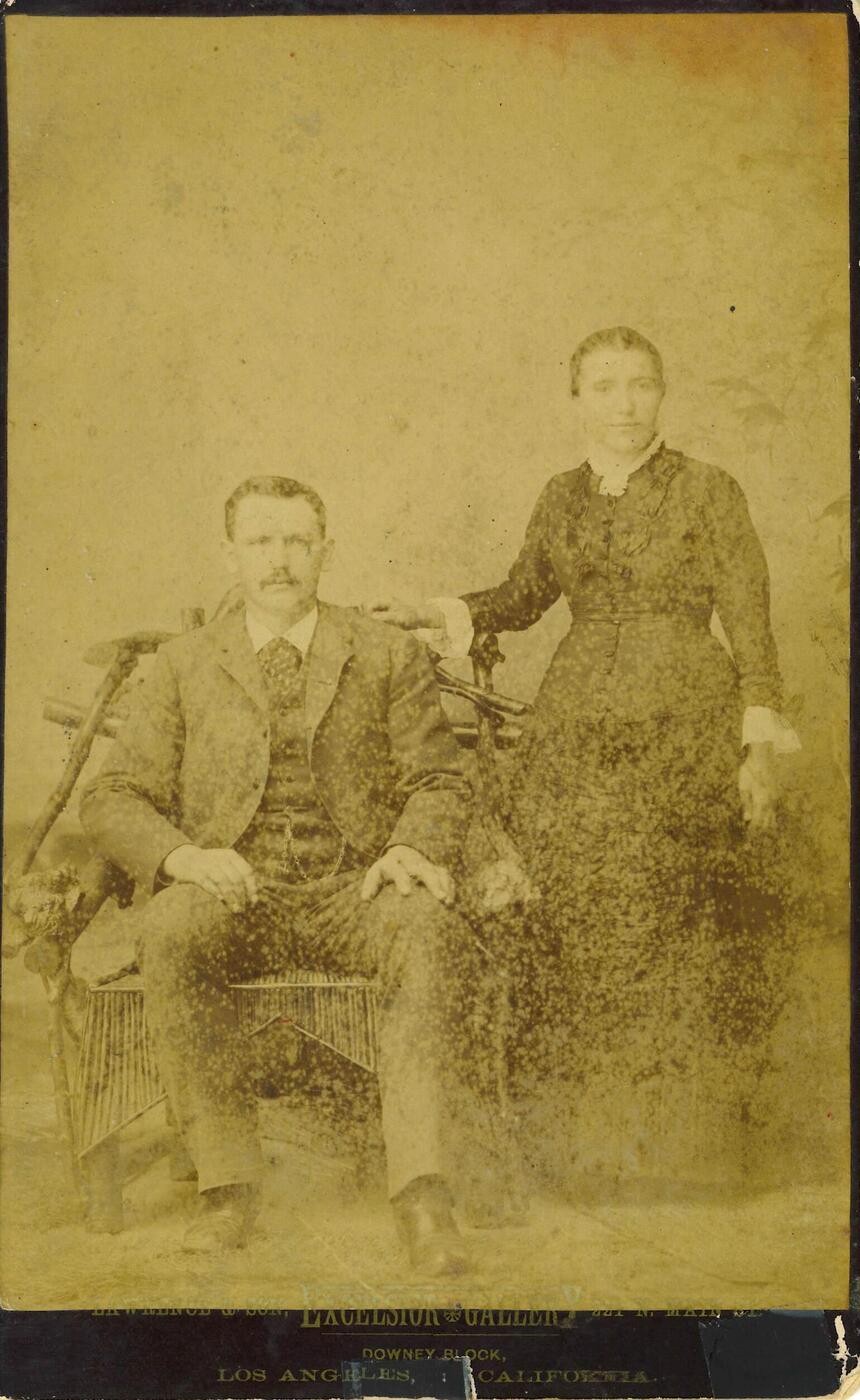

After his heroic act at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station, Rohm continued to fight against the Confederacy in the Appomattox campaign. However, just two days before the war’s end, on April 7th, 1865 during a charge in Farmville, Va, Rohm was hit in the head with a minie ball wounding him greatly. Although he survived his wounds, Rohm became permanently deaf in his left ear. On June 15th, Rohm was honorably discharged from the military and sent back to his home in Juniata County, Penn.

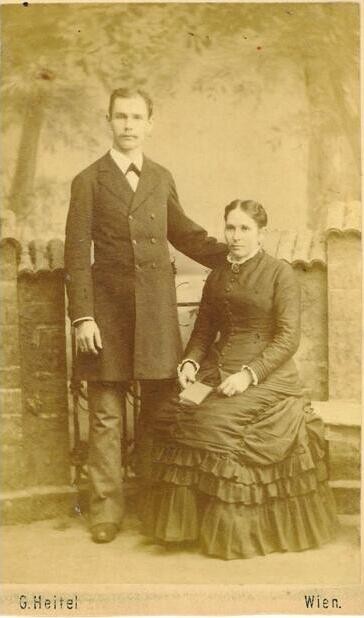

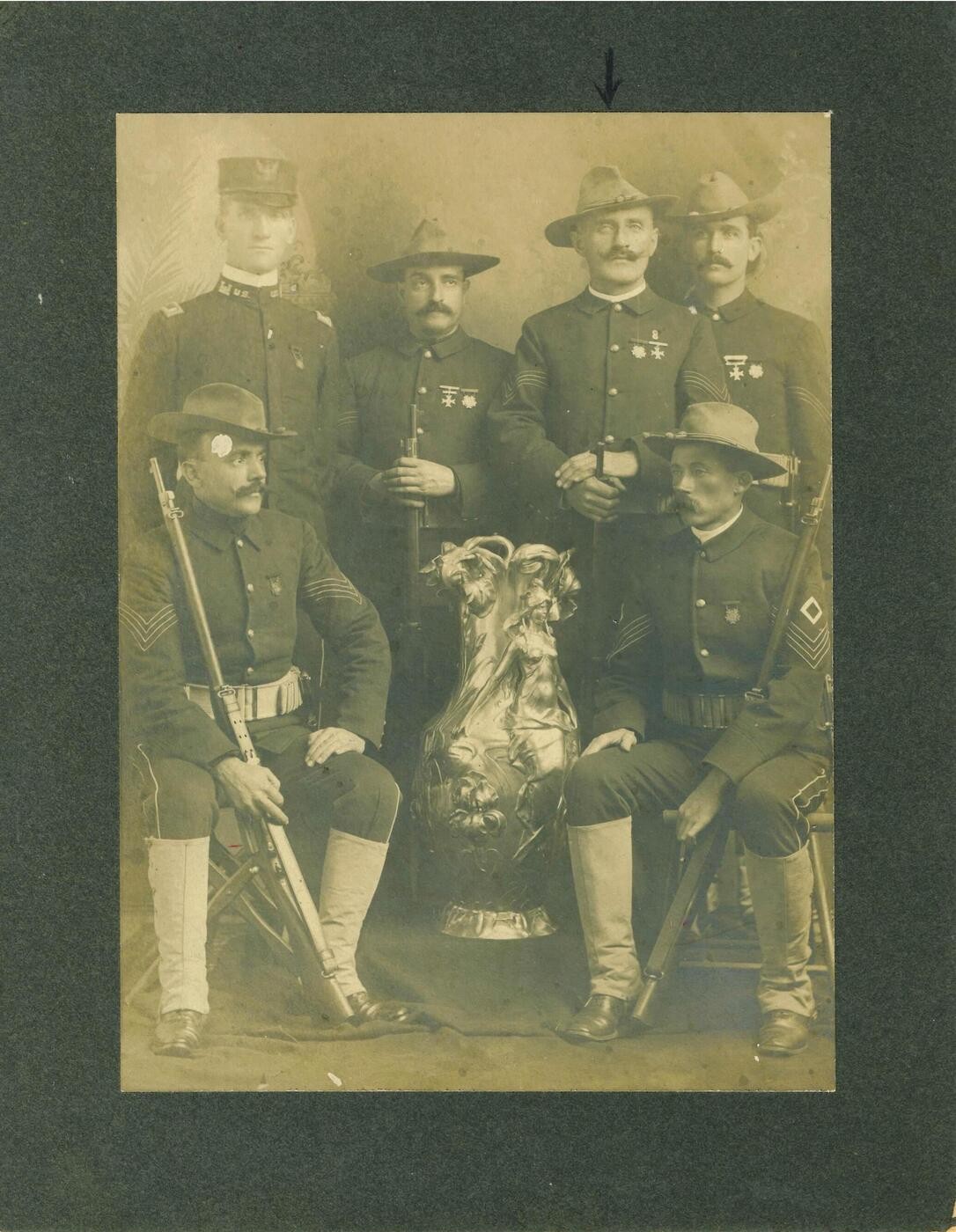

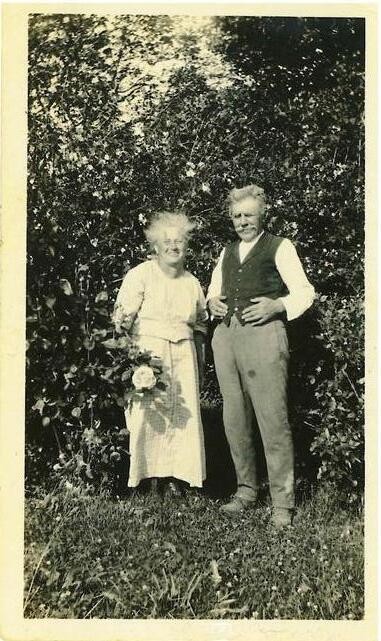

After his honorable discharge from the United States army, Rohm married Mary Lindsay and would go on to raise seven children with her in Juniata County. In 1887, twenty-two years after the war, newly elected governor, James A. Beaver appointed Rohm to the park police at the Pennsylvania State Arsenal. Ten years later, Rohm would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station and his act of service in saving the life of a wounded officer. Rohm continued his employment with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Public Grounds and Buildings department and in 1912 was promoted to sergeant in the Capitol Police.

In November of 1917, Rohm fell ill while on guard at the Pennsylvania State Capitol Complex and was transported to Harrisburg’s Polyclinic Hospital, however, a couple days later Ferdinand F. Rohm would pass away at the age of seventy-four. His body was laid to rest at the Westminster Presbyterian Cemetery in Mifflintown, Penn.

By Luke Romeo Alley