Henry “Hank” Welzel

Biography

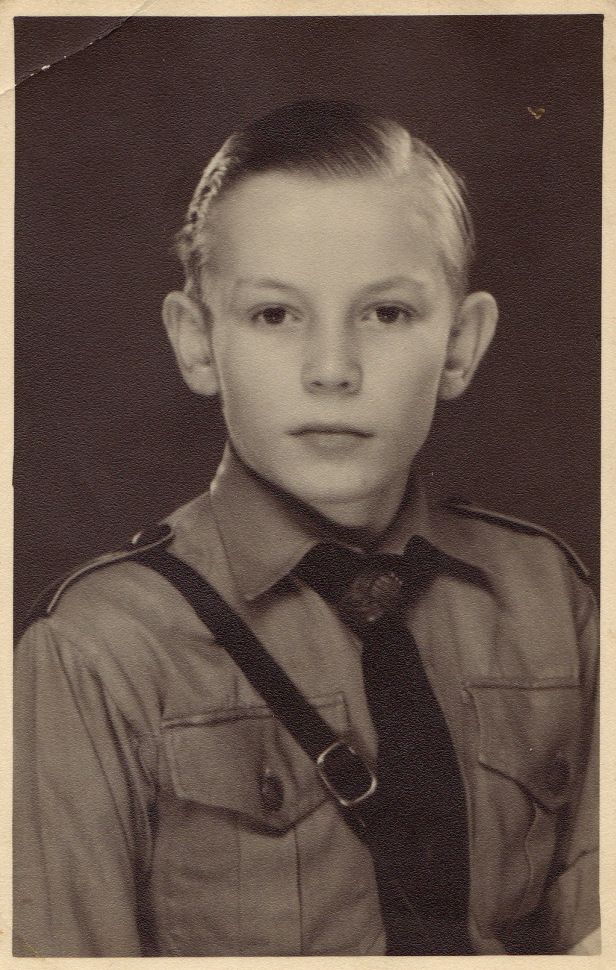

Hank Welzel’s parents immigrated to America in the early 1900s and settled in Lyria, Ohio where Hank was born in 1926. However, the family would not stay there much longer, returning to their home country of Germany when Hank’s father entered into a contract to paint enamel just two years after the birth of his son. Though he was born in America and thus, an American citizen, Welzel could not escape the policies and programs of the Nazi regime that were mandatory for all German children. As a result, he was forced to become a member of the Hitler Youth, and was part of many other war efforts, such as working in a chemical factory when he was 14, while simultaneously being prepared for work in firing squads.

As World War II continued and the Nazi forces met stark resistance on both the western and eastern fronts, the government resorted to opening up their draft pools. As a result, Welzel was drafted into the Nazi army aged just 16. He attended basic training for the infantry, followed by preparation for his main role as a medic. He trained in a field hospital, helping to treat the injured coming back from the east, before being assigned to a unit in Italy. He was the only medic for his unit that was made up of around 300 men. After nearly a year of defending a small pass near Florence, his unit was captured by American forces and taken as POWs back to America, specifically to Camp Rucker in Alabama. Later in life, Hank reflected fondly on his time at the camp, during which he spent most of his days playing soccer with and against the other POWs. However, it was not always fun and games, as he had to hide his American citizenship and identity from the other prisoners and his capturers for his own safety and to avoid being seen as a traitor.

At the end of the war in 1945, Welzel was taken back to Europe to take part in the rebuilding of the continent’s economy, settling in France as a factory worker. In 1949, Hank was given his release and went to find the rest of family who were living in East Germany. After a couple of months, he decided to return to his birth country of America via the U.S. Embassy in Paris. He came to Connecticut to stay with cousins, and quickly decided to enlist in the Marines to completely distance himself from his past over which he had had no control, and to prove to himself that he wasn’t a traitor. Despite his willingness, Welzel was denied entry into the Marines because he had not been living in America for at least a year. This requirement would be waived a few months later with the outbreak of the Korean War when he was drafted into the U.S. Army to serve in a second war for a different country, just a couple months after he turned 24.

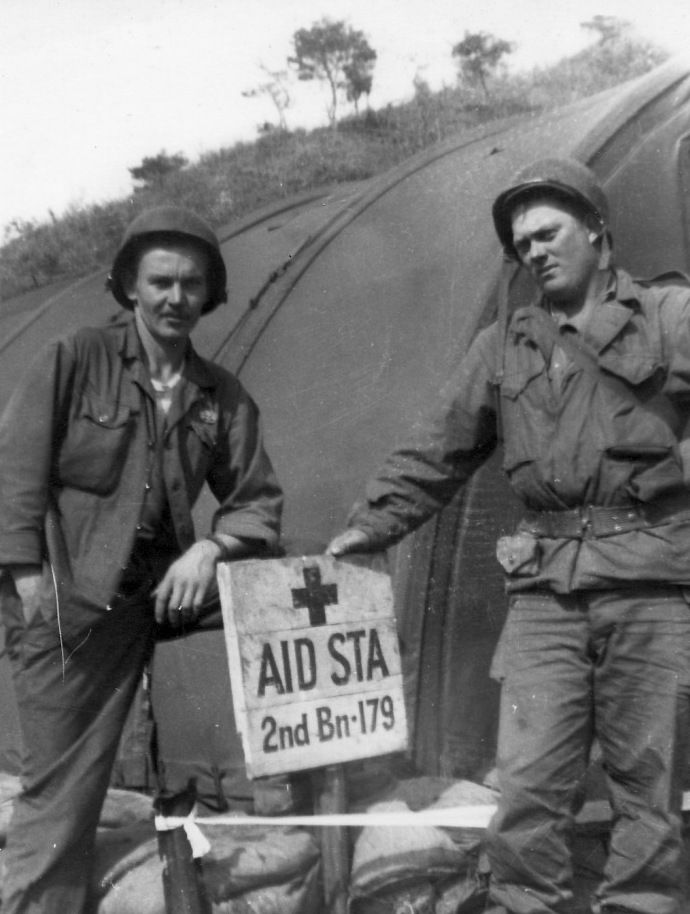

Already an experienced medic, Hank Welzel was quickly assigned that same role for the Americans. In late 1951, he joined the 45th division of the Oklahoma National Guard and shipped out to Korea. He served as a frontline medic in Korea, stabilizing acute injuries so the injured could more safely be sent behind the lines for full treatment and tending to minor ailments in order to send the soldiers back to their posts. In addition to his duties as a medic, every few nights Welzel would join up with around 25 other soldiers in his regiment to go on patrol. Having fun while also using tactical stealth, Welzel and another German-American soldier would communicate over radio on patrol in a rare eastern German dialect, an uncrackable code for the likely listening enemy.

Although he tried to make patrol as fun as possible, going on patrol was still a dangerous task and one of Hank Welzel’s most harrowing personal experiences occurred while out on patrol. Stationed around Pork Chop Hill in South Korea, an area just south of the current Demilitarized Zone that has many small streams and rivers all around, Welzel and his unit were forced to cross the waters as most had no bridges and it was dangerous to cross the always-watched bridges—if there even was one. While crossing a shallow river in the winter, they noticed that Chinese soldiers were all around them. In order not to draw attention and spark an unwanted skirmish, they stood in freezing water that was impossible to keep out of their shoes after a while. Once the enemy cleared from the area, Welzel’s patrol unit had to walk back over a mile to base and only then could they dry and heat their feet. Welzel came out of the situation with severe frostbite to both feet, but chose to treat it himself to avoid spending time in the hospital because his mission was to treat and protect the wounded, and he could not do that from a hospital. He took this to heart and returned to America after his deployment with shrapnel in his arms and legs from shielding injured soldiers who were waiting to receive treatment from explosions.

Hank Welzel was discharged from the Army in December of 1952, nearly a year after his arrival in Korea. Along with the shrapnel in his body, he came back home with both a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star medal. He was never sure what exact instance earned him the incredibly high honors, whether it was his frostbite or shielding the wounded from shrapnel, but he was immensely proud to have served his country. After his time in the Army, he went back to the Northeast, where he married his wife, Gloria, and raised five children with her in Massachusetts and Maine. He put his military life behind him, working in the fiberglass and plastics industry, but struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder for over forty years before receiving treatment. He found one of the best ways to deal with his past was to be open and share his story. In May 2019, at the age of 92, Hank Welzel passed away, but his story and experiences as a brave and heroic German-American remain to this day.

Written by Thomas Crain