FROM OUR COLLECTION

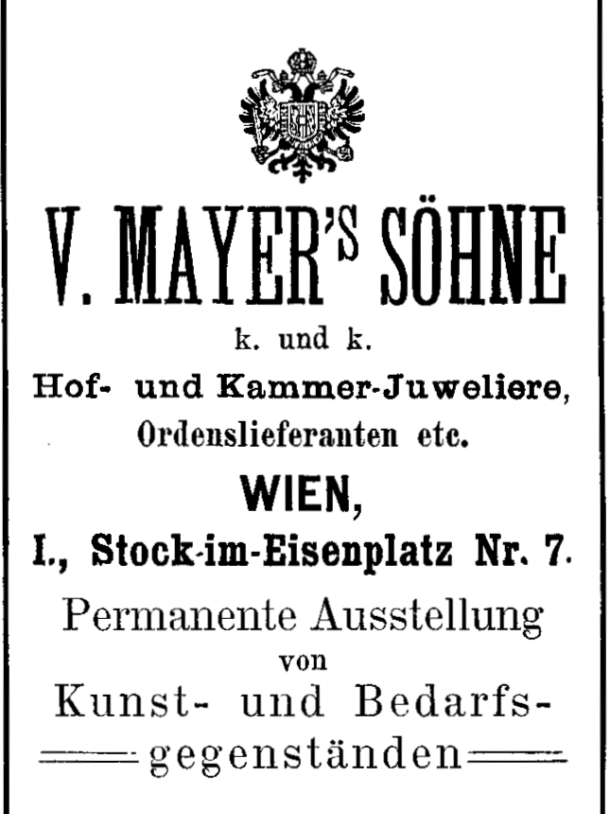

Vincenz Mayer’s Söhne

Located in the heart of the city, across from the famous St. Stephen’s Cathedral at Stock-im-Eisen-Platz 7, they created all the Imperial Austrian Orders, along with some smaller pieces such as the Marianna Cross and Red Cross decorations. In addition, the family-owned company made insignias for various other countries including Greece, Romania, and Serbia. After the death of Vincenz Mayer in 1865, his three sons, Vincenz, Joseph, and Franz successfully took over the

business. Their mark can often be identified as a “VMS” which is usually framed. Their products were of such high quality, that they received an imperial and royal warrant and were appointed K.u.K. (royal and imperial) court jewellers

and later chamber jewellers to the Emperor and Empress. Sadly, the downfall of many European monarchies and the economic crisis following World War I resulted in a greatly reduced market for court decorations and military orders, and V. Mayer’s Söhne closed its doors forever in 1922.

Their work can still be found in Viennese antique shops, and at least one very special piece made its way across the Atlantic more than 120 years ago, and is now a prized piece of our collection.

Tucked away in the museum’s music corner, situated between the Wurlitzer baby grand piano, an impressive 350-pound bronze bust of composer George Frideric Handel, and a Victorian upright piano by German American instrument maker Charles Stieff sits a gilded trophy in a modern plexiglass display case. Upon closer inspection,

the inquisitive viewer realizes that the decorative platter, which serves as a foundation, features a circle of multi-colored gemstones, which are repeated at the top of the cup.

The cup’s base showcases four double-headed eagles, the symbol of the Habsburg monarchy, and its front bears an engraved inscription which reads:

Gewidmet von Kaiser und König Franz Joseph I. zum Deutschen Sängerfeste in San Francisco 1910

or

Dedicated by Emperor and King Franz Joseph I for the German Singing Festival in San Francisco 1910

In the late 19th and early 20th century, singing festivals were not only a popular form of comparing vocal prowess, they were tremendously popular modes of entertainment that attracted tens of thousands of people. Singing societies trace their origins to the German-speaking world where students of Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) applied his teachings of social reforms and cultural change to the singing groups they had founded. Pestalozzi’s student Carl Zelter promoted the Sängerbund movement, as it came to be called, throughout Prussia beginning in 1809, and Hans Georg Nägeli, a Swiss composer, music teacher, and songbook publisher, undertook numerous journeys across Germany in the early 19th century to encourage the formation of male singing groups for social reform. European immigrants soon brought the tradition to the North American continent, albeit without the political and educational connotation, and the Philadelphia Männerchor founded by German immigrant Phillip Matthias Wohlseiffer in 1835 became the first

German American singing society organized in the United States where the Sängerfest began to evolve as a form of civic entertainment. Amongst the devoted attendees were several U.S. presidents. On June 15, 1903, President Teddy Roosevelt attended a singing festival of 6,000 individual singers at Baltimore’s Armory Hall. All 9,000 seats were sold out, and Roosevelt delivered an address praising the German culture and the Sängerfest tradition.

The San Francisco event, which took place over several days in early September of 1910 was by all accounts a grand affair with dozens of singing groups, choruses, soloists, thousands of audience members, and several valuable prizes for the winners in different categories. The two most coveted prizes were donated by the monarchs of Germany and Austria-Hungary, Emperor William II and Emperor Franz Joseph I respectively.

The cups were presented by the Austrian and German consuls as the newspaper San Francisco Call reported on Sept. 6, 1910.

So far, so good. Finding relevant information about the competition was the easy part. The cup arrived at our museum in 2017, carried by a delegation of San Francisco-based Freundschaft Liederkranz in whose possession it had been for decades.

However, as historians and curators we wanted to learn about the cup’s origins. How and why did Emperor Franz Joseph donate a trophy? And who had created this stunning piece? As a frequent visitor to Austria, I got in touch with various museums and art historians in Vienna. Nobody had ever seen or heard of the cup although there was general agreement that its style was representative of Austrian Fin de Siecle artisans. I was advised to look for a maker’s mark which could help us trace the cup’s mysterious origins. Intrigued, we carefully examined both the cup and the platter, and alas, carefully hidden on the platter’s rim were three tiny letters: VMS.

Equipped with this new knowledge, it was back to the proverbial drawing board and scouring online archives. Soon it was revealed that VMS stood for Vincenz Mayer’s Söhne, an iconic Viennese jeweller known for producing jewelry, silverware, medals, and decorations, such as the Order of the Iron Crown and Imperial Austrian Order of Franz Joseph. Founded in 1810, this firm was almost as well known as Rothe.

1910 photo displaying the tropy

Photo Credit: Austrian National Archive