Frederick von Weissenfels

Revolutionary War

Biography

In 1728, Frederick Baron de Weissenfels, or Frederick von Weissenfels, was born in Elbing, Prussia, known today as Elblag, Poland, which is located southeast of Gdansk. Keeping with Prussian tradition, young Frederick began military training, and did so under one of Europe’s best generals: King Frederick the Great. Serving under the same man who trained him, Weissenfels fought in the Second Silesian War, his first experience in battle. Before the eventual final installment of the Silesian campaign, Weissenfels sought new opportunities outside of his home country and took a commission in the British Army as a lieutenant in 1756. The British frequently turned to foreign officers to fill similar positions in their North American colonies, so Weissenfels made his way across the Atlantic.

Weissenfels joined with the British at a critical juncture because the French and Indian War was beginning. He joined up with the 60th Royal American Regiment as one of only around 50 foreign, commissioned officers of the regiment. Of his most notable contributions, he was a participant in the Battle of Fort Ticonderoga, which was a French-held fort in northern New York in an area which both colonial empires claimed, under General James Abercrombie in 1758. A year later, he served under General James Wolfe in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham which took place on a plateau outside of the walls of Quebec City. In the end, Weissenfels and the rest of the British forces captured Quebec City. As the war began to wind down, many British troops were transferred to the West Indies to fight against Spain and its colonies because the Spanish decided to back France late in the war. Weissenfels was a part of the forces sent to Cuba in 1762 and he fought in the capture of Havana, Cuba in 1762.

Upon the end of the war in 1763, the British Army reduced its numbers and Frederick Baron de Weissenfels was one of the many soldiers cut from the ranks. He was given half-pay and decided to start his civilian life in New York instead of returning to his native Europe. In that same year, he took an oath of loyalty to the British crown and became a naturalized citizen of Great Britain, a feat which he earned through his military service for the empire. As a civilian, Weissenfels held a couple different jobs as a storekeeper and even operated a ferry across Long Island Sound.

In 1775, at the outset of the revolution, Frederick Baron de Weissenfels turned his back on the British he previously fought for, and wrote to the Provincial Congress of New York to offer up his military services and expertise in support of the colonies. By the end of the year, he was appointed brigade major under General Richard Montgomery in the Battle of Quebec which was a heavy and early defeat for the Continental Army. Despite the defeat, a couple months later, in early 1776, Weissenfels was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the Third Battalion of the Second New York Regiment. With the Third Battalion, Weissenfels served alongside General George Washington at the Battles of White Plains and Trenton, as well as in the captures of Burgoyne and Monmouth. After these stretches of battles, his regiment engaged in a few battles with Native Americans in the now controversial Sullivan Expedition of Upstate New York. Following this expedition, the Continental Army was reduced and Weissenfels was then appointed by the State of New York to a position leading a regiment of state troops, a position he would hold until the war’s completion.

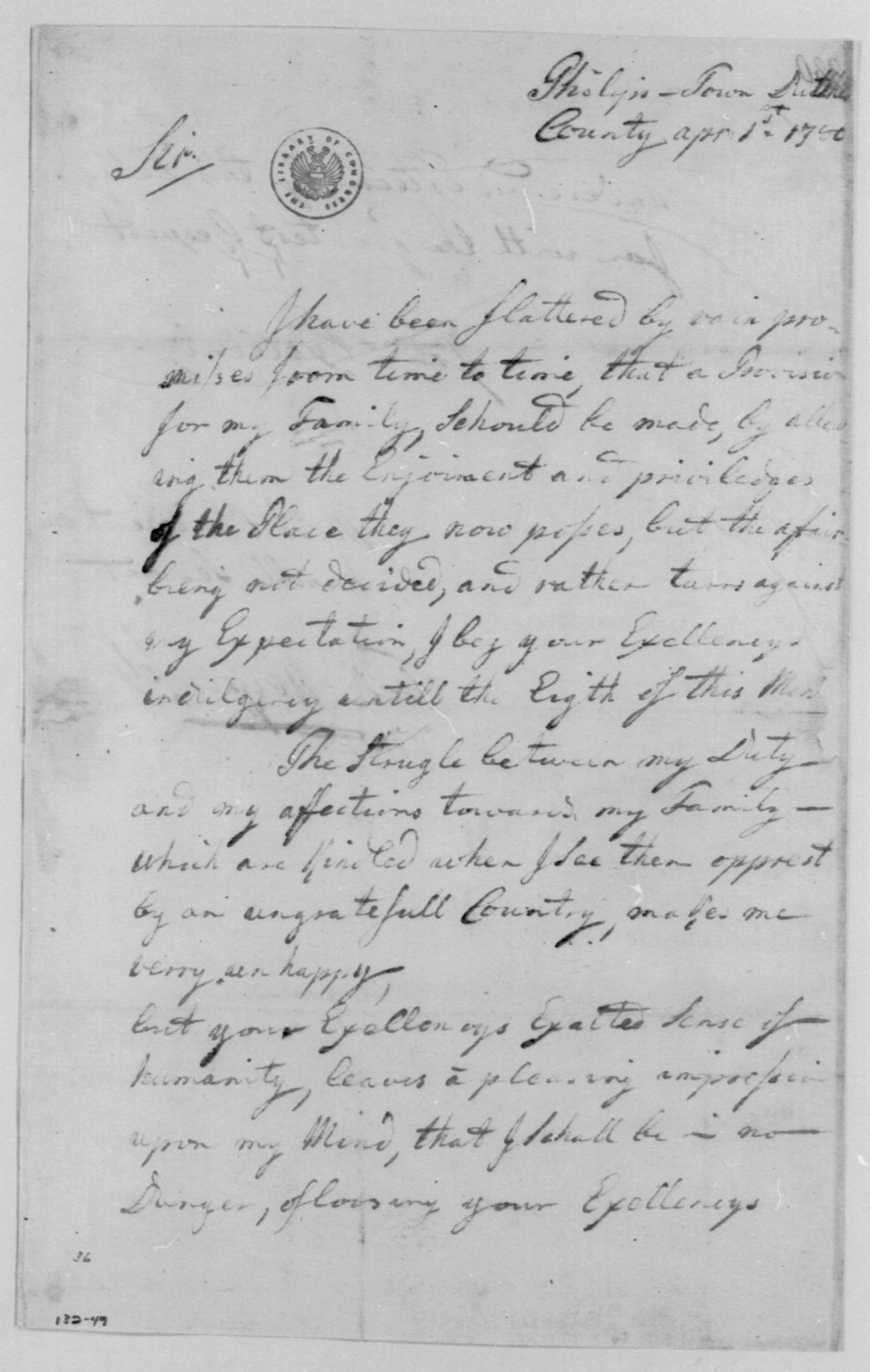

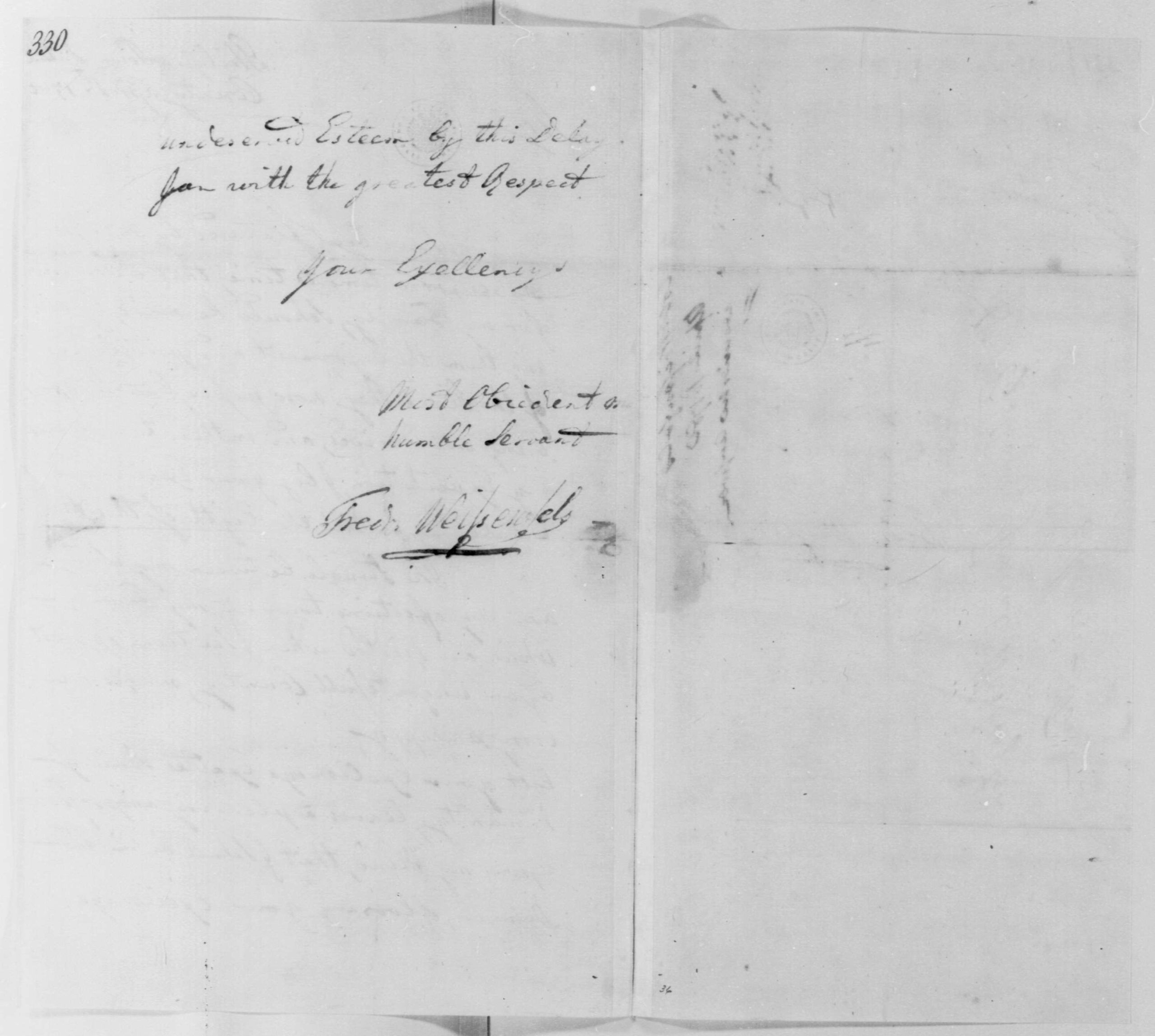

It was through the aforementioned battles that Weissenfels acquainted himself with the Continental Army’s highest ranking officer and the future first president of the United States, George Washington. Over the years, the two men exchanged correspondence, of which thirteen letters survive in the National Archives as part of the Papers of George Washington collection. One letter was written by Weissenfels to Washington on April 1, 1780. Here is a transcript of the letter:

“Sir

I have been flattered by vain promisses from time to time, that a Provision for my Family, Schould be made, by allowing them the Enjoiment and priviledges of the Place they now posses, but the affair being not decided, and rather turns against my Expectation, I beg your Exellencys indilgency untill the Eight of this Mon⟨th⟩.

The Strugle between my Duty and my affections towards my Family—Which are Kindled when I See them opprest by an ungratefull Country, makes me verry un happy.

but your Exellencys Exalted Sense of humanity, leaves a pleasing impression upon my Mind, that I Schall be in no Danger, of loosing your Exellencys undeserved Esteem by this Delay. I am with the greatest Respect Your Exellencys Most Obiedent most humble Servant

Fredk Weissenfels”

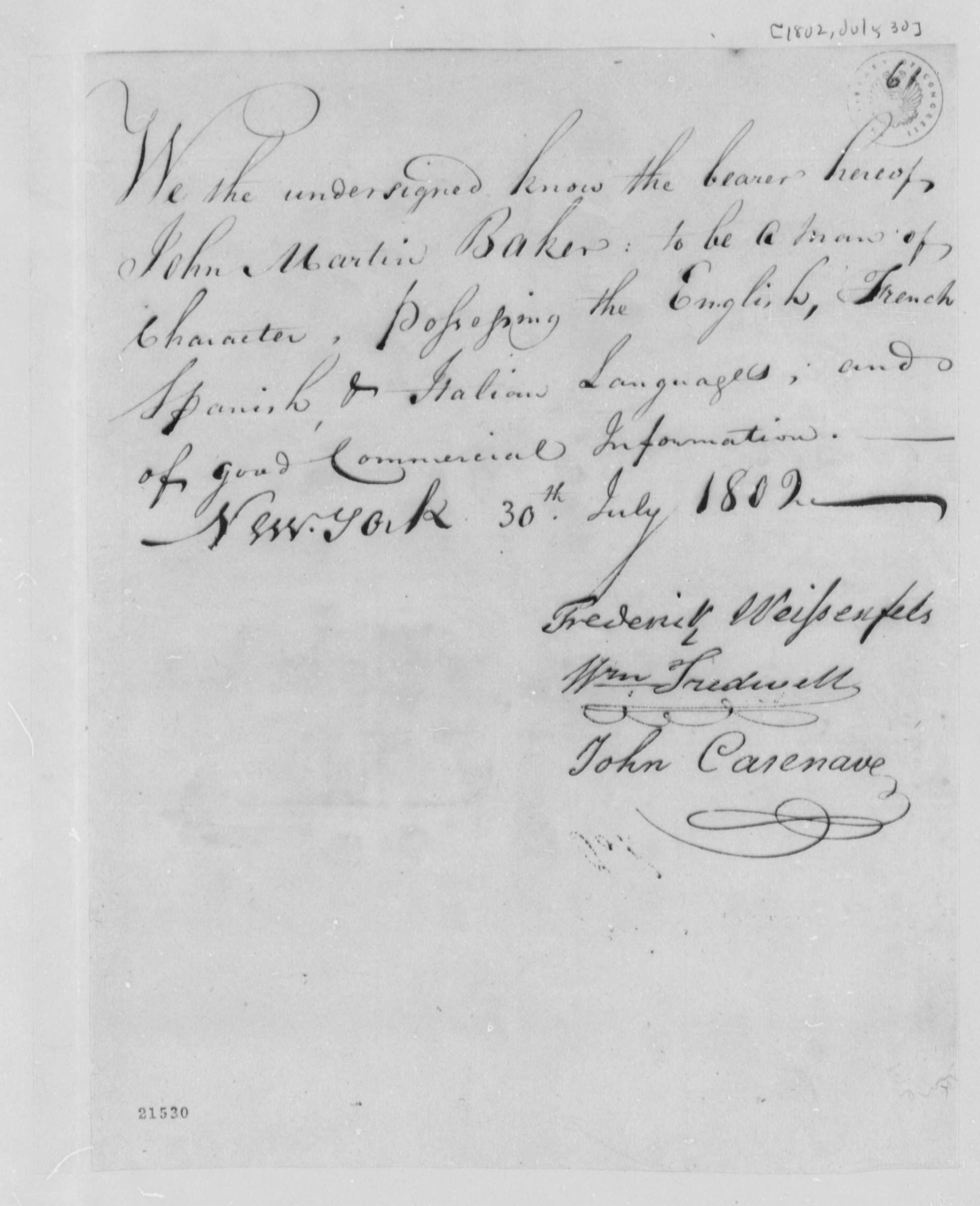

This letter was a plea to Washington to grant him an extended leave from battle to tend to personal matters, despite his desire to return to serving his country. A gifted soldier, Weissenfels did not fare as well as a civilian. He had given up his half-pay and promised tract of land as a discharged English soldier without receiving the same from the new republic, which left him in dire need of money. His financial struggles became even more apparent when he made appeals to Washington in 1788 to receive a patronage position in the government or to be given funds by Congress, appeals that the General denied.

In the 1790s, Weissenfels was a founding member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal organization to maintain friendships made in the Revolutionary War, memorialize those who served, and to provide financial assistance to needy members, help which Weissenfels denied. Instead, he worked various jobs around New York City, living in the country that he fought to create. Late in his life, he moved to New Orleans and took up a minor role as a police officer in the city. On May 14, 1806, however, Frederick Baron de Weissenfels would pass away in New Orleans, and was honored with a military burial fitting for a German-American soldier who assisted in the creation of the nation.

Written by Thomas Crain