75th Anniversary of the Berlin Airlift – How the U.S. and Royal Air Forces Saved Berlin’s Blockaded Residents

German-American Heritage Museum of the USA™

Follow us

Thank you to our partners and supporters for making this exhibit possible:

2024

“When we refused to be forced out of Berlin, we demonstrated to the people of Europe that with their cooperation we could act, and act resolutely, when their freedom was threatened.”

~ President Harry S. Truman ~

75th Anniversary of the Berlin Airlift – How the U.S. and Royal Air Forces Saved Berlin’s Blockaded Residents

When dawn broke in Berlin, Germany on June 24, 1948, the outside temperature was cool enough to keep people snuggled into their beds and blankets. At 6 o’clock local time that morning, Soviet troops had enforced a complete blockade of the city and its inhabitants, including the areas controlled by Western allies. Berliners and Allied troops alike awoke in a place that was akin to an open-air prison: an area that was completely closed off, and could no longer be reached by road, rail, or water.

Post-World War II Germany was a divided and occupied country, and Berlin was no exception. . The Allies, consisting of the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union, had each claimed distinct territories, which were initially administered through the Allied Control Council. The German capital city with is approximately three million inhabitants was no exception. It too was jointly occupied by the Allied powers and divided into four sectors despite being geographically located in the Soviet zone. All four countries were entitled to special privileges in Berlin, and this included the Soviet sector of Berlin, which was legally separate from the rest of the Soviet zone.

The blockade did not come as a complete surprise as relations between the Allied Powers had been plagued by growing tensions. The UK’s wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill had already warned the world in his 1946 speech in Fulton, Miss. that the alliance forged during the Second World War was breaking down: “From Stettin on the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” Behind that curtain, the Soviets had tightened their control, and had expanded their sphere of influence by forming a ring of satellite states. In February of 1948, a Communist faction seized control of the government in Prague, Czechoslovakia, and shortly afterward, the Soviet Union imposed arbitrary restrictions on who and what could enter Berlin. These access curtailments, which for example included a temporary halt on coal shipments, were designed to create supply shortages and to instill fear in a population that was still dealing with rationing and a ravaged infrastructure. Of course, these actions also led to increased tensions between the Allied powers, and eventually to the breakdown of the initial plan of governing Germany as a single unit. The question of whether the Western occupation zones in Berlin would remain under Western Allied control or whether the Soviets would take over Berlin resulted in the first crisis of the coming Cold War. A failed joint attempt to establish a new currency proved to be the final straw, and prompted the Soviet powers to block off Berlin.

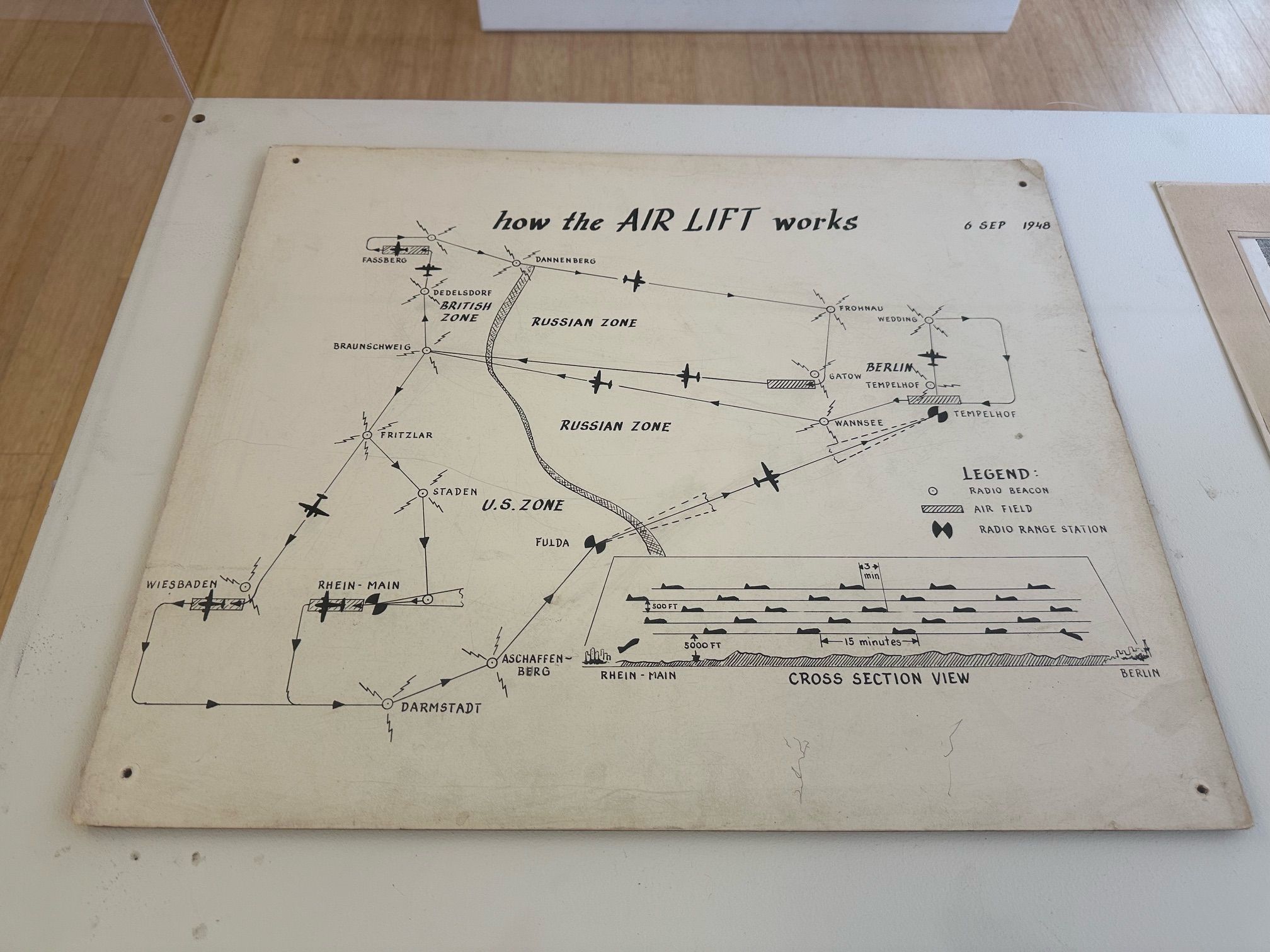

The Western allies did not want to engage militarily, but not acting would mean abandoning the city to the Soviets. In response, the United States and the United Kingdom created a daring plan to airlift food, fuel, and other supplies from air bases in western Germany. The Truman administration rightfully considered these flights a humanitarian mission, and so the the United States launched “Operation Vittles” on June 26, with the United Kingdom following suit two days later with “Operation Plainfare.”

Despite the desire for a peaceful resolution to the standoff, the United States also sent B-29 bombers to the UK, which were capable of carrying nuclear weapons. The beginning of the airlift proved difficult, and Western diplomats asked the Soviets to seek a diplomatic solution to the impasse.

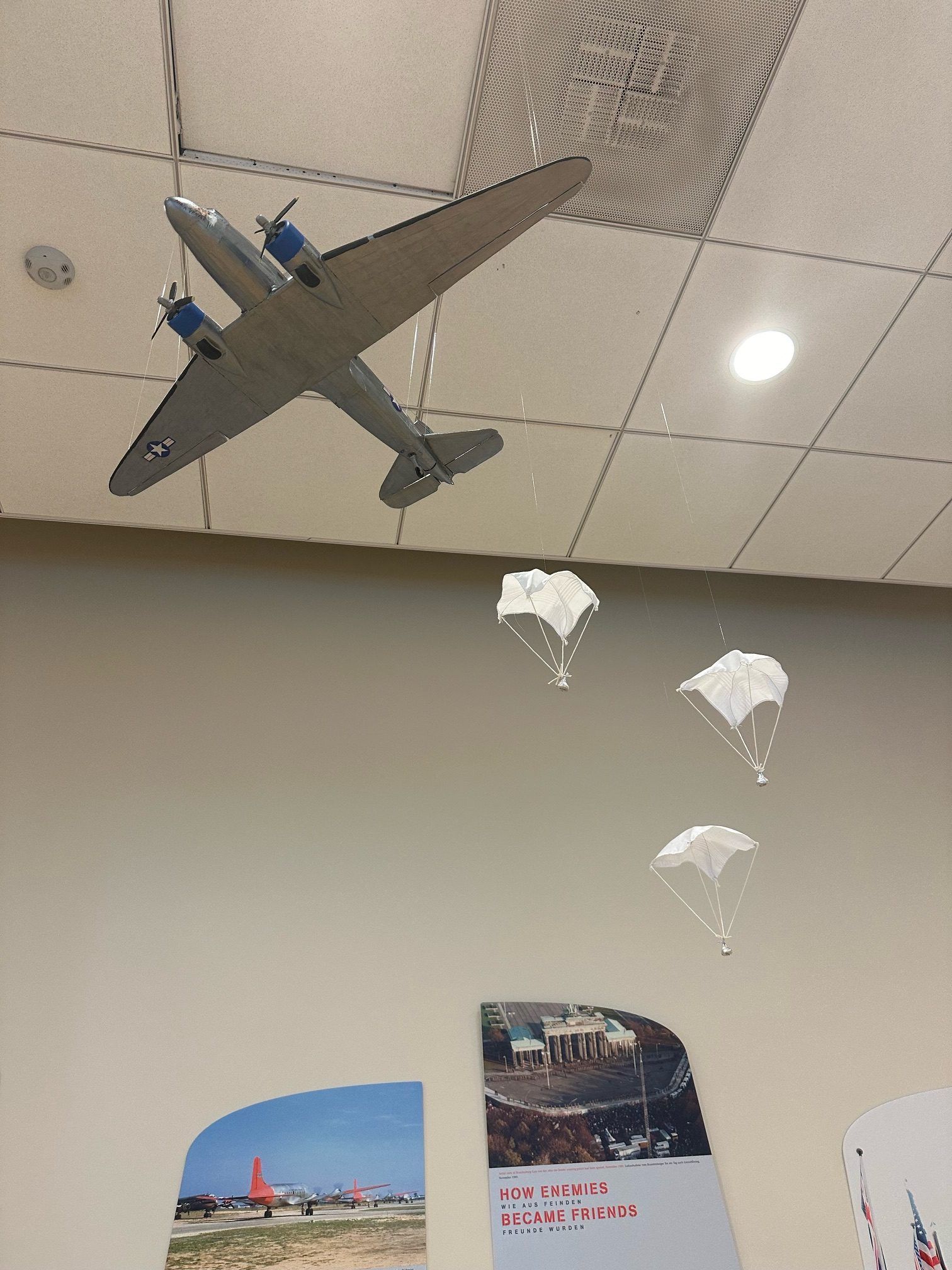

In time, the airlift became ever more efficient, and the number of planes increased. At the height of the campaign, a plane landed every 45 seconds at Tempelhof Airport. By spring 1949, the Berlin Airlift had proved successful, and the Western Allies had demonstrated that they could sustain the operation indefinitely. At the same time, the Allied counter-blockade on eastern Germany was causing severe shortages, which, Moscow feared, might lead to political upheaval. On May 12, 1949, Moscow lifted the blockade of West Berlin. The Berlin Crisis of 1948–1949 solidified the East-West division of Europe. Shortly before the end of the blockade, the Western Allies created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Whilst the airlift was a military and humanitarian success, it did not come without a price. A total of 101 people lost their lives, including 31 Americans and 40 Britons. Furthermore, 17 American planes and eight British aircraft crashed during the operation causing most of the deaths.

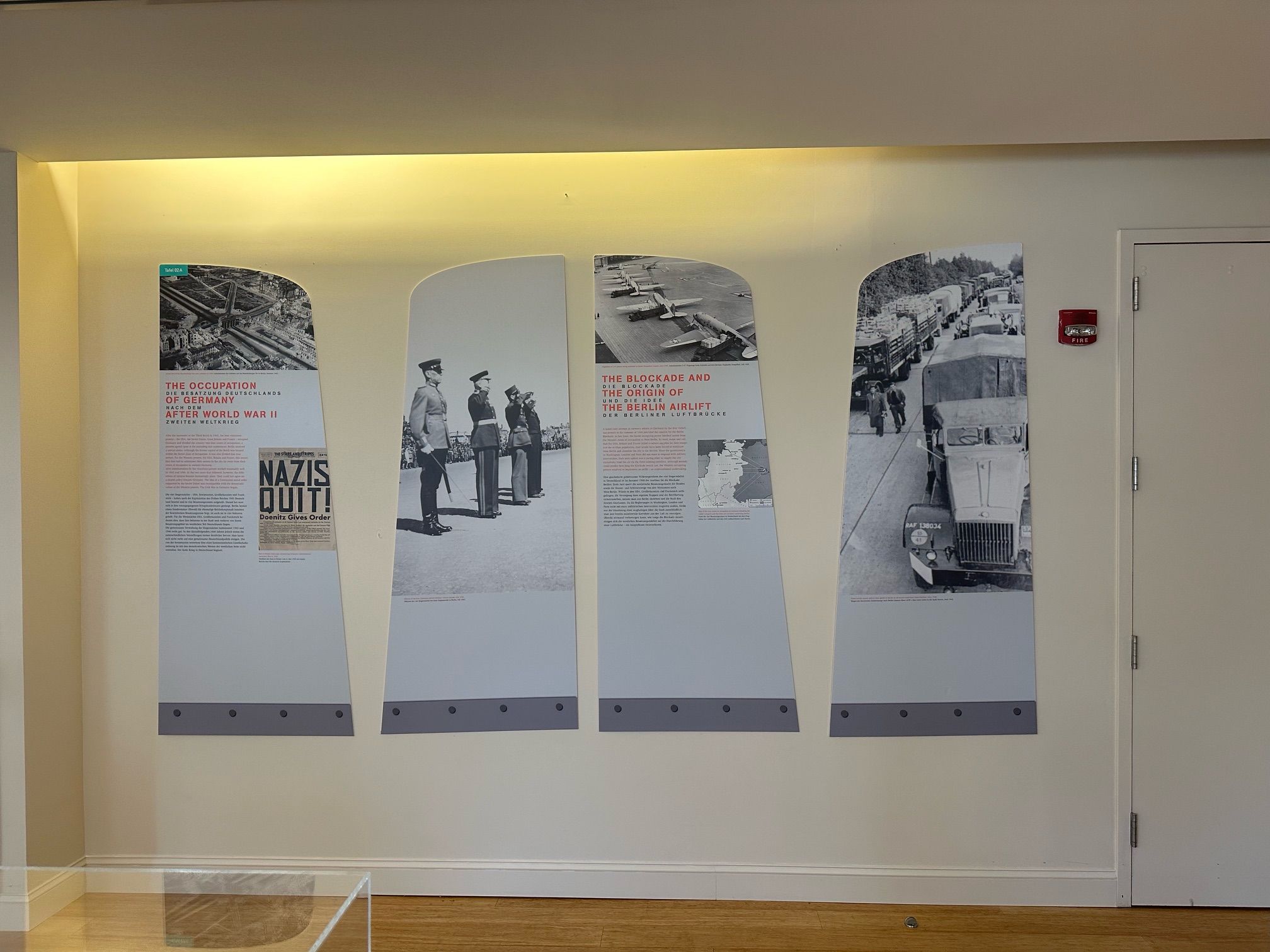

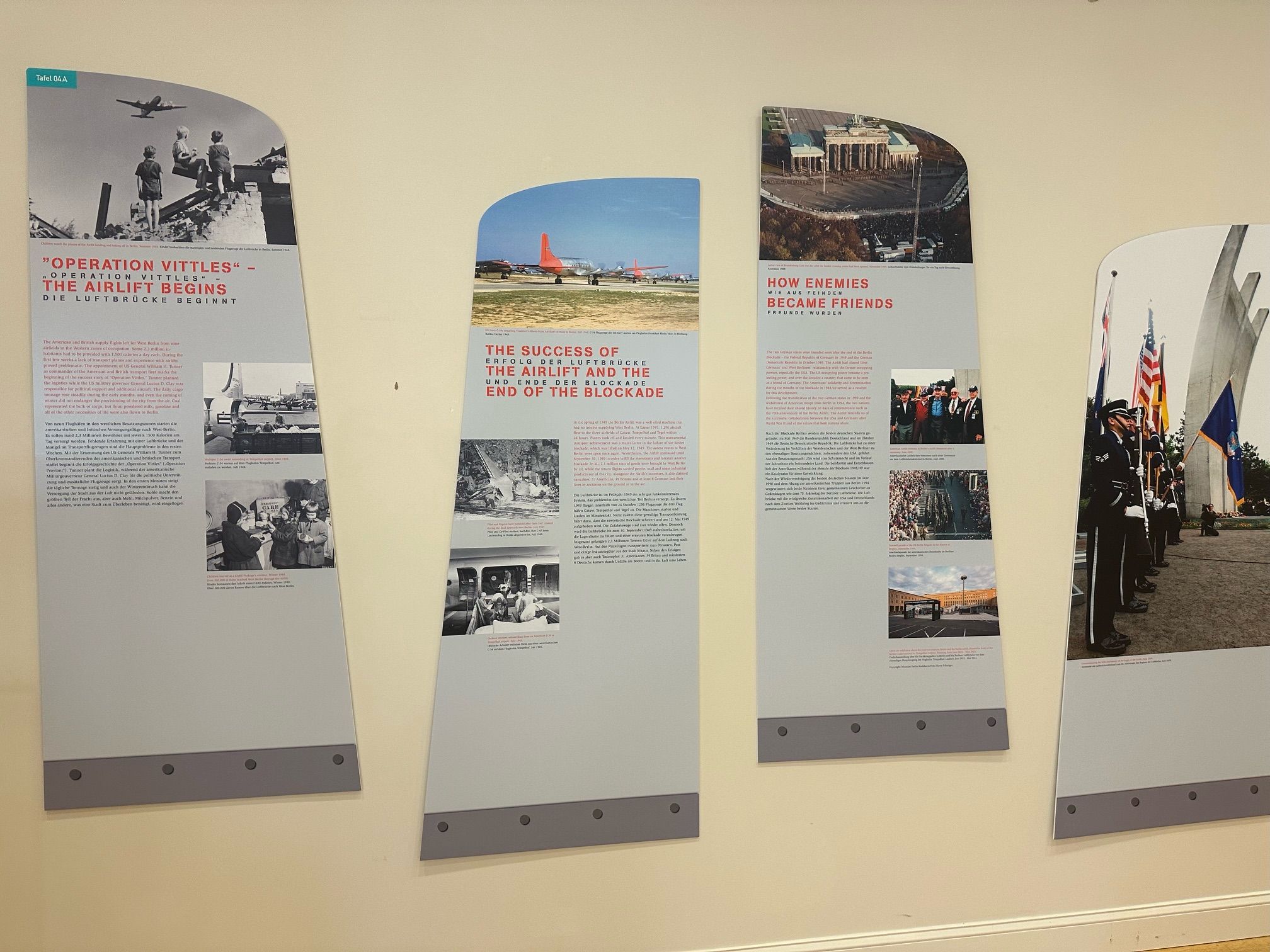

GAHF’s goal is to educate about the Berlin Airlift and to ensure that this tremendous humanitarian effort that turned former enemies into friends and partners is not forgotten. The exhibit is a mix of panels designed by the Allied Museum in Berlin and various artifacts including photos, letters, newspaper reports, quotes from people who lived through the airlift, and models of the famous C-54 planes that served as the Berlin Airlift workhorses. As our audience is not just limited to Washington, DC, we’re also having a digital component that can be accessed online. These resources are not just limited to the Allied Museum, but include foundations, the Smithsonian Institutes, the Library of Congress, the City of Berlin, and others.

Links:

https://www.airlift-berlin.com/introduction.html

http://www.spiritoffreedom.org/

https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/online-collections/berlin-airlift

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/berlin-airlift

https://www.berlin.de/ba-tempelhof-schoeneberg/ueber-den-bezirk/gedenken/artikel.358187.php

Information

-

Admission Exhibit

GAHF Members, seniors, & students (with ID)

$7.50 -

Admission Exhibit

General public

$10