Werner Kleeman

World War II

Biography

Werner Kleeman was born into a Jewish family in a small town near Würzburg, Germany in 1919. As the Nazis took power, the family began planning for their escape from Germany by having distant relatives sponsor their immigration requests. On Nov. 9, 1938, he left for the American consulate in Stuttgart with his older brother who had been summoned upon approval of his visa request. That night, they stayed in their hotel as the Nazis began their destruction of Jewish businesses, homes, and synagogues on Kristallnacht. Werner’s brother immediately fled the country, leaving Werner to drive back home to his distraught mother in their mostly demolished home. His father and siblings had already been arrested and upon arrival, he was arrested and joined his father in a nearby prison. Eventually his father, a veteran of World War I, was granted release due to his prior service, but Werner and other young Jews were bussed to the Dachau concentration camp. Dedicated to making it out against all odds, Kleeman kept his health and just before Christmas 1938, he was released from Dachau and taken to nearby Munich where he was informed that he could go home and wait to leave Germany because his immigration request was granted.

A couple weeks after his release from Dachau, he secured passage to England in January 1939, a safe place to wait for his visa to enter America. After getting settled in London with the help of a cousin, Werner began working unpaid jobs due to his immigration status, but made connections in the business community, allowing him to get fed and earn some money on the side. While in London, his parents and two youngest siblings joined him in the Spring of 1939 to wait for their American visas to arrive, gaining release from Germany in a similar fashion as Werner. After 11 long months of waiting, Werner Kleeman was finally informed by the American consulate that his visa was ready, so he bought the cheapest ticket to New York in December 1939.

Upon arrival, Werner went to Long Island to stay with another cousin, and he got a job in a Brooklyn department store’s stockroom, getting to work like any other immigrant, though his journey there was different than many who came before him. A few weeks following Werner Kleeman’s arrival in New York, his parents secured their American visas and came to New York on the same boat. However, Werner would be the only one to stay in New York because his parents and younger siblings went to live in Baltimore where his older brother had established residence. This did not bother him much, though, because he knew he was lucky to get out of Germany, and even luckier that his family was similarly safe and free, a rare accomplishment by the end of World War II for the vast majority of German Jews.

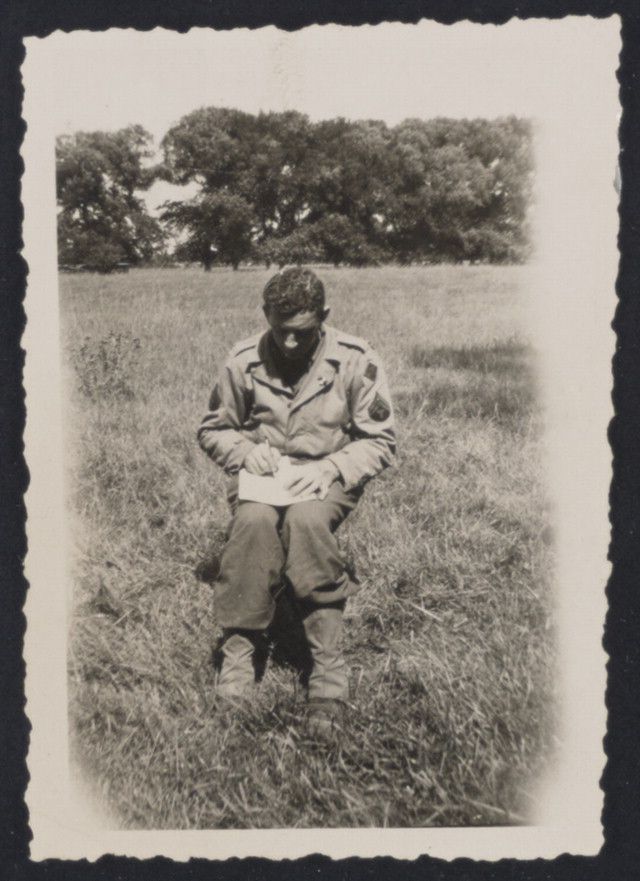

After over two years of living and working in New York, America entered into the war and in June 1942, Werner was drafted into the U.S. Army. He was sworn in on Governor’s Island in New York City, then taken to Camp Upton on Long Island for intake and medical examinations. Despite only being in the Army for a few days and not even gaining citizenship yet, wearing the uniform made Kleeman feel American, but chiefly he felt he was “better off being there than being in Germany in a concentration camp.” After intake, Werner and his fellow draftees were put onto a troop train heading to Camp Wheeler near Macon, Georgia for 90 days of basic training. Many of the draftees were immigrants, like Werner Kleeman, and after the 90 days, they were taken to the federal courthouse in Macon and sworn in as an American citizen. After gaining citizenship, Kleeman was sent to Augusta, Georgia to join the Fourth Infantry Division. In late 1943, the Fourth was sent to the Florida coast to gain amphibious landing training; unbeknownst to the soldiers they were preparing for the D-Day invasion.

Following amphibious training, Werner’s division was transferred to multiple bases before finally being sent to England in January 1944, awaiting the crossing of the English Channel. He had been trained to land with the first wave of soldiers on the beaches of Normandy, but by yet another stroke of luck in March 1944, his knowledge of the German language was noticed, and he was promoted to the role of translator, attached to division headquarters and assigned a Jeep, removing him from the front lines. When General Eisenhower finally gave the orders to land at Normandy on the morning of June 6, Werner stayed on the boat with the other division leaders, hearing the gunfire and shells, hoping that nothing would hit his boat. After the first wave landed, fought, and cleared the beach, Werner Kleeman came ashore Utah Beach with artillery shells still flying, yet he felt relieved to have reached France safely thanks to the sacrifice of the men in the first wave. After landing in France, he spent time as a translator in the liberation of France, Belgium, and Germany. He and the other German speakers were reassigned to stay in Germany instead of following the Fourth to Japan, and eventually was transferred to his former hometown of Gaukönigshofen.

In Gaukönigshofen, Werner Kleeman wanted to rectify the horrors of his last months in Germany. By speaking with a trusted German friend, he gathered the names of 11 of the Nazi policemen that took part in the actions of Kristallnacht, had the policemen arrested, and forced them to sign written confessions for their roles on that abhorrent night. He knew that they would eventually be released under the almost nonexistent German justice system at the end of the war, but Werner got all the justice he needed. After completing his personal mission back in Germany, he was furloughed and allowed to go back to New York in late 1945. After a few months in and out of different hospitals across America, he was given a medical discharge due to acute hearing loss suffered during the war. After his discharge from the Army, Werner started an interior design business out of his home where he lived with his wife and two daughters. In 2007, at the age of 88, Kleeman decided to publish From Dachau to D-Day: A Memoir about his experiences surrounding the war. Werner Kleeman passed away in 2018 at the age of 98, but his legacy as a true German-American hero, and his life of ultimate perseverance, lives on to this day.

Please click here to listen to a recorded interview and to view correspondence at the Library of Congress.

Written by Thomas Crain